A small History

Before the Wheat Penny appeared in 1909, the United States one-cent coin had already spent decades evolving in design, metal composition, and meaning. The change from the Indian Head penny to the Wheat Penny wasn’t just a routine redesign. It reflected a growing belief that American coinage should be more artistic, more modern, and more intentional about the story it told—especially as the nation entered a new century.

The Indian Head cent was introduced in 1859 and remained in circulation until 1909, giving it one of the longest runs of any U.S. cent design. It was created by James B. Longacre, the U.S. Mint’s Chief Engraver. The coin’s obverse shows a classical figure of Liberty wearing a Native American-style headdress. Although the nickname “Indian Head” stuck, the portrait was not meant to depict a specific Native American person. Instead, it followed a 19th-century artistic habit of combining symbolic Liberty with imagined Indigenous motifs—a choice that would later be criticized, but was widely accepted at the time.

Like many coins, the Indian Head cent also reflects the practical realities of manufacturing. The earliest issues were struck in a copper-nickel alloy, which could appear lighter in color and was sometimes difficult for the Mint to strike sharply. During the American Civil War, pressures on metal supplies and the need for more efficient production helped drive a shift. In 1864, the cent’s composition changed to bronze, which generally struck better and proved more practical for mass circulation. Small design adjustments followed over the years, but the overall look stayed familiar—a coin most Americans recognized instantly.

By the late 1800s, however, a new conversation was gaining momentum: were America’s coins too plain, too old-fashioned, or simply not beautiful enough? Compared with many European coins of the era, U.S. designs were increasingly viewed by artists and critics as uninspired. This was not just an aesthetic complaint. Coin designs were seen as miniature public monuments—objects handled daily by nearly everyone, carrying national symbols into everyday life.

That belief found a powerful champion in President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt took office in 1901 and strongly supported improving the artistic quality of U.S. coinage. He pushed for bold redesigns and encouraged the involvement of prominent sculptors and medalists. His broader aim aligned with cultural movements of the time, including the American Renaissance, which valued classical balance, high craftsmanship, and symbolism in public art. In that environment, redesigning coins felt like a meaningful national project rather than a minor administrative change.

As the idea of coin reform took hold, another historic moment approached: 1909 would mark the centennial—the 100th anniversary—of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. Lincoln had become one of the most admired figures in American history, symbolizing unity, democratic ideals, and moral courage. Putting Lincoln on the cent was both a tribute and a cultural statement: the nation was ready to honor a real person, not just an allegorical figure like Liberty.

This was a major shift. For a long time, American coinage avoided portraits of actual individuals, partly to distance the young republic from European traditions of monarchs on coins. But by the early 20th century, public attitudes had changed. Lincoln was broadly respected across regions and political backgrounds, and the centennial created a clear reason—and a popular opportunity—to do something new.

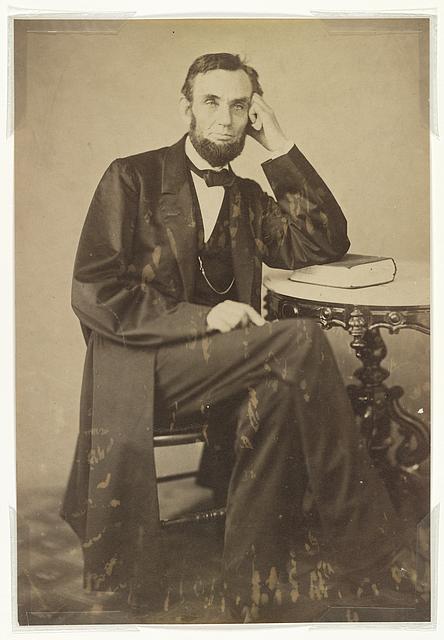

To design the 1909 cent, the Mint selected Victor David Brenner, a sculptor and medalist known for his work with portraits. Brenner had created a well-regarded plaque of Lincoln, and his interpretation appealed to Roosevelt and Mint officials. The resulting Lincoln portrait emphasized realism and quiet dignity. It presented Lincoln not as a distant myth, but as a recognizable human figure—thoughtful, composed, and steady. This realism helped the coin feel modern and personal at the same time.

The reverse design introduced what collectors now call the Wheat Ears reverse: two wheat stalks framing the words “ONE CENT” and “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.” Wheat was a fitting symbol for the era. It suggested growth, stability, and prosperity, and it connected the coin to the agricultural foundation of the country. The layout was simple and balanced—less decorative than some earlier coin reverses, but confident and easy to read.

When the new cent entered circulation in 1909, it drew immediate attention. People noticed the change right away: the familiar headdress and wreath were gone, replaced by Lincoln’s profile and the wheat-stalk border. The coin was widely embraced, but it also sparked a quick controversy over Brenner’s initials, “VDB,” which appeared prominently at the bottom of the reverse. Critics argued the initials were too visible, and the Mint removed them later that same year. They would return in a smaller form on the obverse in 1918. This short-lived “VDB” episode became part of the Wheat Penny’s origin story—and one reason 1909 cents remain especially interesting to collectors.

In the end, the transition from the Indian Head cent to the Wheat Penny represented more than a design swap. It signaled a new era in American coinage: greater artistic ambition, a stronger willingness to honor historical figures, and a recognition that even the smallest coin could carry big meaning. For a Wheat Penny site, this moment is the perfect starting point—because the Wheat Penny begins as a celebration of Lincoln, a product of reform, and a snapshot of how America wanted to see itself in 1909.